Honoring Drew Zingg, a great guitarist and old friend

A podcast, concert celebrating his music in NYC on June 18 (info below), and some links to his playing

There are moments when someone shows us what’s possible— at the beginning, when it counts. It can be a recording. But it’s more powerful as a physical encounter. Someone who demonstrates what mastery can be, opens a path. We see or hear our future rumbling out in front of us, like a train we’re trying to catch up with.

The engine of our lives is created by an accretion of these moments. Whether by art, love, the heavens, or any other impossible passion.

For some a moment occurs while watching a stage show. But the more impactful experience might be where someone is sitting right across from you. In my case, it was a guitarist named Drew Zingg. At age 13 in 1972 we ended up at the same summer camp as roommates. On the first day of camp a few people gathered around in our room. The pals he’d come to camp with, including my next door neighbor Bill Block, knew how good a player he was, and they asked him to break out his Strat. If memory serves, he played the entire version of “Freedom” from Cry of Love. Or maybe it was “The Wind Cries Mary,” solo and all. I was bug eyed. Recall this music was fresh, a couple years old, and very few people could knock off Hendrix with ease. They all then encouraged me to play. I had suddenly lost all interest in playing the guitar. I can still feel the fear, the tension in my chin and shoulders. I knew what the score was, he was way more advanced than me, but I couldn’t back out. I managed to summon my Guyatone from its hiding place and choke out what I’m sure was a fairly sad version of, let’s say, “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.” Everyone was very kind, especially Drew. That’s what we do for each other. It mattered.

Whatever we were supposed to be doing at camp, running around sweating our asses off swinging rackets, running races and stuff, I avoided, as did Drew, whenever possible. I paid close attention though when Drew opened his guitar case. Those four weeks at summer camp sent me on my path, the one I’m still on today.

On April 10 Drew Zingg died in his home in San Francisco. He was not a player that everyone knew. But those who knew him loved him. The outpouring on social media amazed me. And all I could think about was, “If only he could see this…”

Drew was one of the go-to gigging guitarists all through the 80’s and 90’s in NYC. His highest profile gig was with Steely Dan between 1993 and 94. He was born for this gig. He had their tunes figured out note for note the days after the records came out, I watched it happen. He played them perfectly. Drew went on to perform with a lot of other luminaries, including Boz Scaggs, Michael McDonald, David Sanborn, and Shawn Colvin. I saw him with most of those acts. He always sounded fantastic. He had his own sound, and you can’t say that about everybody.

As fate would have it, we never lived in the same town. By the time I finally moved to New York he came to where I’d been, California! But whenever we got together to play it was like being a kid again—just like the first time we jammed in 1972. Even back then he had a powerful sense of time, a ferocious right hand, a great groove. His playing ended up in that fertile space between rock, R&B, and jazz. It all was the same thing in his hands. Perhaps that sounds somewhat normal today. But there weren’t that many people doing that back in the mid 70s. A short list might be, Buzz Feiten, Larry Carlton, Skunk Baxter, Denny Dias, Hiram Bullock, Eric Gale, Cornell Dupree. Drew learned from all of them, especially Buzzy. People don’t know enough about Buzzy. (I’m going to go deep into Buzzy’s music in another post.) But Drew took his sound, put his foot on the accelerator, and took it to the moon.

I came across an interview with the original Steely Dan guitarist, Denny Dias, recently. He said something that’s plain to see if you know those early tracks. “I was a jazz musician, playing rock music.” In fact, he said he studied with Billy Bauer, who was one of the great bebop guitarists. This, to me, is a crossroads where many of my favorite guitarists have lived. And Drew felt the same way. He found the means to bring Charlie Parker, Larry Carlton, Hendrix, and Cornell Dupree together.

All of us who were Drew’s friends felt a sense of celebration and pride when he climbed on stage with Steely Dan. There’s something wonderful about seeing a friend “make it.” We all strive so hard towards greatness, few make it there, and fewer still are visibly rewarded. In the 90s, Drew was the talk of the town.

How stunned I was, then, when Becker and Fagen fired him. I guess it kind of hurt to see a friend sidelined, especially somebody who did it so well. He was never given a reason. There’s no job security in this business, that’s for sure. (And no doubt his replacement was excellent, too.) Drew went on to play with other well-known people. Although I never played in a band with him, he was reputed to be an extremely dependable team player who could light a band up, and it showed in how often he was hired.

Interestingly, he almost never led his own bands, he was not a composer and only made one of his own records. He was essentially talked into it by a group of close friends who helped him put it together in 2011. It’s a fine document of what he’s capable of. I asked Drew why he was hesitant to make this record, and quite surprisingly his response was, “I wasn’t ready.” Ready? He was in his mid 50s, and as far as everyone else was concerned, had been ready for decades.

You can buy that record here:

And there’s where the story gets more difficult. Being humble is one thing. And Drew was humble to the core. But holding yourself too close to an ideal of perfection is a danger zone.

I hadn’t seen Drew in many years when I sat down with him last summer to interview him for my podcast series. I was out on the West Coast at my brother’s memorial service. Along with many laughs, some catching up, we played and talked. I had a subtle sense that he was nervous. Shy perhaps. He’d always been hard to read. His fingers seem to be shaking when he began to play. Some of his comments were self -deprecating. Meanwhile, sitting across from me was one of the best guitarists I ever met, and he had lost absolutely none of his ability. Hell, I was the one who should’ve been nervous— and I was.

Here is the podcast:

Drew said something to me before I got the tape running that surprised me. He told me that he had reached a point in his life where he felt like he had given himself away to all the countless people that he worked for. That in a sense he had never found Himself. Now I’m paraphrasing a little here, but I’m pretty sure this is the gist of what he meant.

He told a story about recently getting on stage with one of the stars that he played with, how the show opened up with him playing a solo on an instrumental tune, and as the singer walked out he whispered in Drew’s ear, “Don’t burn.” Drew was shocked. This person was telling him to rein it in, don’t be yourself. I’ve thought about this a lot since I heard the story. Perhaps from the singer’s perspective it was justifiable. But to be an incredibly capable sidemen for four or five decades and still be told how to play… that’s rough. Especially when that sideman is making the singer’s band sounds so damn good.

It provoked an existential moment for Drew. As he says in our podcast, he realized that many great players had been fired by band leaders, Jimi Hendrix, Chet Atkins, Danny Gatton, all had been fired from a job. They tended to overwhelm the main act. He laughed about it, but I felt as if there was a deeper discomfort he was experiencing. He was no doubt aware that he had resisted going out on his own, investing fully in himself, and now 67 years old.

From the outside, his career seemed enviable. But human nature being what it is, we all seem to want more and need more than what we have. There’s something that happens when you reach your 60s. I’ve seen it in several friends, many of them musicians. And I guess I may have occasionally felt it myself. You look back on whatever you’ve accomplished, and what you see all too clearly is what didn’t happen, not what did. You feel that you’re running out of time, and you look back towards things you might’ve done differently. Regrets lurk in the shadows like feral dogs. Others around you laud your accomplishments, but on some days those accomplishments seem small indeed. I’m projecting some here, I really did not know Drew well enough to be sure that he felt all these things. But I’ve met plenty of guys my age who did.

Art is central to the identity of the artist. It, almost more than anything, is the guarantor of satisfaction and happiness. And unfortunately, it is no guarantee at all. Rather, our art is ephemeral, undependable, meretricious, and most of us develop a love /hate relationship with it over time. We aim for love, but it can be a tough battle. No matter how well-known you are, no matter how much you accomplish, there are deep, doubts, insecurities, dark days.

In any given era, in any given town, there are a handful of masterful players who make those around them sound good, who make a band leader happy. I salute them. They deserve our undying respect and love. Many of these folks none of us will ever know. Drew had the distinction of moving up the food chain into a position where a lot of people knew about him. But the spotlight fades for us all.

Drew continued to play fantastic music for anyone he worked with. I just spoke with a band leader from the West Coast, who told me how much he depended on Drew in his band, how lucky he felt to play with him, and how devastated he was that he was gone.

When I heard he died I was grateful that I had done this interview with him. At the same time, I was perplexed that it taken me so long to organize and post it, almost a year. Something held me back. Whatever those reasons are, I will keep them to myself. Meanwhile, there’s a permanent record of wisdom that he imparted. One of the most enjoyable parts of our talk is when he discussed finding joy in the instrument anew during the pandemic. Having hit something of a dead end before that, that sideman fatigue, he focused solely on what he cared about, the music that meant the most to him. He singled out Django Reinhardt, whose music he took a deep dive into.

It has been good for me to put all this on paper, and I hope that it serves the greater purpose of keeping his memory and contribution to the world of guitar alive. I guess I better stop writing and go back to learning a few of his licks. Drew might be surprised that I will miss him so much. I believe he was one of those people who was unaware of how much he was appreciated.

If you knew our friend Zingg, you experienced his sense of humor. So let me end there. He was one of the funniest people I ever met. A well-seasoned, well-timed, dry wit, always ready with a punch line. Even at age 13, he seemed to look at life with a raised eyebrow and bemused smile, something that native New Yorkers almost seem to be born with. I treasure the chuckles almost as much as the notes.

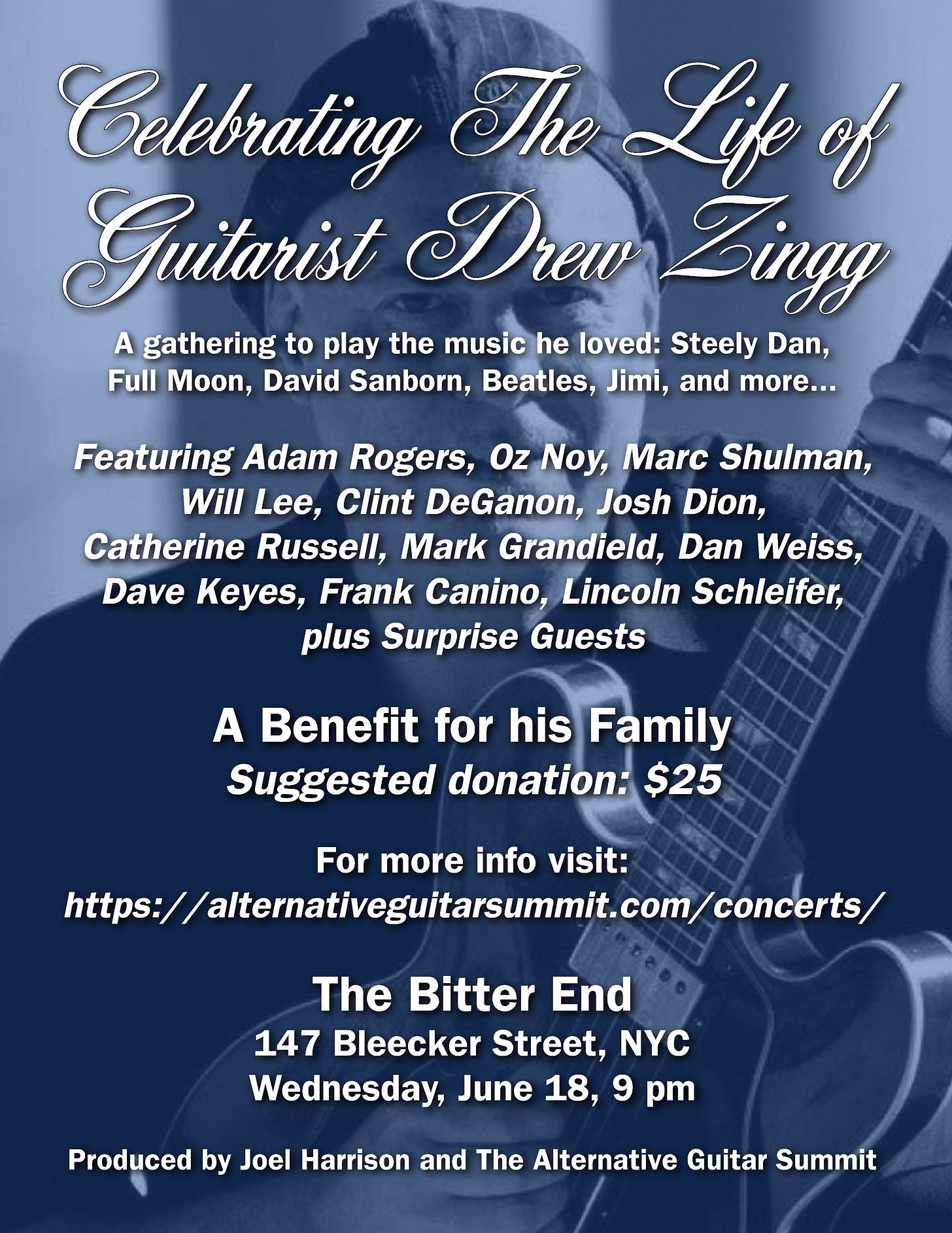

Please join us for a celebration of his music and life in New York City on Wednesday, June 18 at the Bitter End. A who’s who of his associates will be on hand to play music that he loved. You can see who’s going to be there by clicking on the link.

https://bitterend.com/#/events/141542

Here are some tracks which feature him at his best:

Pretzel Logic: Donald Fagen’s Rock n’ Soul Revue

My Old School: Steely Dan

Tennessee St.: Drew Zingg

Live With Mona Lisa Overdrive (Recorded by Drew’s brother in a small club. The opening solo on this is quite staggering!)

With David Sanborn (live)

Got to about 13 min. in

Thank you

thanks James